Osteopontin (OPN), also known as bone /sialoprotein I (BSP-1 or BNSP), early T-lymphocyte activation (ETA-1), secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1), 2ar and Rickettsia resistance (Ric),[5] is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SPP1 gene (secreted phosphoprotein 1). The murine ortholog is Spp1. Osteopontin is a SIBLING (glycoprotein) that was first identified in 1986 in osteoblasts.

| Osteopontin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Osteopontin | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00865 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR002038 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00689 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The prefix osteo- indicates that the protein is expressed in bone, although it is also expressed in other tissues. The suffix -pontin is derived from "pons," the Latin word for bridge, and signifies osteopontin's role as a linking protein. Osteopontin is an extracellular structural protein and therefore an organic component of bone.

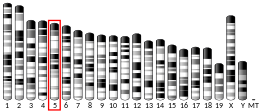

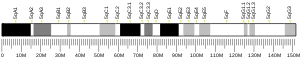

The gene has 7 exons, spans 5 kilobases in length and in humans it is located on the long arm of chromosome 4 region 22 (4q1322.1). The protein is composed of ~300 amino acids residues and has ~30 carbohydrate residues attached, including 10 sialic acid residues, which are attached to the protein during post-translational modification in the Golgi apparatus. The protein is rich in acidic residues: 30-36% are either aspartic or glutamic acid.

Structure edit

OPN is a highly negatively charged, heavily phosphorylated extracellular matrix protein that lacks an extensive secondary structure as an intrinsically disordered protein.[6][7] It is composed of about 300 amino acids (297 in mouse; 314 in human) and is expressed as a 33-kDa nascent protein; there are also functionally important cleavage sites. OPN can go through posttranslational modifications, which increase its apparent molecular weight to about 44 kDa.[8] The OPN gene is composed of 7 exons, 6 of which containing coding sequence.[9][10] The first two exons contain the 5' untranslated region (5' UTR).[11] Exons 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 code for 17, 13, 27, 14, 108 and 134 amino acids, respectively.[11] All intron-exon boundaries are of the phase 0 type, thus alternative exon splicing maintains the reading frame of the OPN gene.

Isoforms edit

Full-length OPN (OPN-FL) can be modified by thrombin cleavage, which exposes a cryptic sequence, SVVYGLR on the cleaved form of the protein known as OPN-R (Fig. 1). This thrombin-cleaved OPN (OPN-R) exposes an epitope for integrin receptors of α4β1, α9β1, and α9β4.[13][14] These integrin receptors are present on a number of immune cells such as mast cells,[15] neutrophils,[16] and T cells. It is also expressed by monocytes and macrophages.[17] Upon binding these receptors, cells use several signal transduction pathways to elicit immune responses in these cells. OPN-R can be further cleaved by Carboxypeptidase B (CPB) by removal of C-terminal arginine and become OPN-L. The function of OPN-L is largely unknown.

It appears an intracellular variant of OPN (iOPN) is involved in a number of cellular processes including migration, fusion and motility.[18][19][20][21] Intracellular OPN is generated using an alternative translation start site on the same mRNA species used to generate the extracellular isoform.[22] This alternative translation start site is downstream of the N-terminal endoplasmic reticulum-targeting signal sequence, thus allowing cytoplasmic translation of OPN.

Various human cancers, including breast cancer, have been observed to express splice variants of OPN.[23][24] The cancer-specific splice variants are osteopontin-a, osteopontin-b, and osteopontin-c. Exon 5 is lacking from osteopontin-b, whereas osteopontin-c lacks exon 4.[23] Osteopontin-c has been suggested to facilitate the anchorage-independent phenotype of some human breast cancer cells due to its inability to associate with the extracellular matrix.[23]

Tissue distribution edit

Osteopontin is expressed in a variety of tissue types including cardiac fibroblasts,[25] preosteoblasts, osteoblasts, osteocytes, odontoblasts, some bone marrow cells, hypertrophic chondrocytes, dendritic cells, macrophages,[26] smooth muscle,[27] skeletal muscle myoblasts,[28] endothelial cells, and extraosseous (non-bone) cells in the inner ear, brain, kidney, deciduum, and placenta. Synthesis of osteopontin is stimulated by calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3).

Regulation edit

Regulation of the osteopontin gene expression is incompletely understood. Different cell types may differ in their regulatory mechanisms of the OPN gene. OPN expression in bone predominantly occurs by osteoblasts and osteocyctes (bone-forming cells) as well as osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells).[29] Runx2 (aka Cbfa1) and osterix (Osx) transcription factors are required for the expression of OPN[30] Runx2 and Osx bind promoters of osteoblast-specific genes such as Col1α1, Bsp, and Opn and upregulate transcription.[31]

Hypocalcemia and hypophosphatemia (instances that stimulate kidney proximal tubule cells to produce calcitriol (1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3)) lead to increases in OPN transcription, translation and secretion.[32] This is due to the presence of a high-specificity vitamin D response element (VDRE) in the OPN gene promoter.[33][34][35]

Osteopontin (OPN) expression is modulated by Schistosoma mansoni egg antigen.[36]

Schistosoma mansoni egg antigens directly stimulate the expression of the profibrogenic molecule osteopontin (OPN), and systemic OPN levels strongly correlate with disease severity, suggesting its use as a potential morbidity biomarker. Investigation into the impact of Praziquantel use on systemic OPN levels and on liver collagen deposition in chronic murine schistosomiasis revealed that Praziquantel treatment significantly reduced systemic OPN levels and liver collagen deposition, indicating that OPN could be a reliable tool for monitoring PZQ efficacy and fibrosis regression.[37][36]

Extracellular inorganic phosphate (ePi) has also been identified as a modulator of OPN expression.[38]

Stimulation of OPN expression also occurs upon exposure of cells to pro-inflammatory cytokines,[39] classical mediators of acute inflammation (e.g. tumour necrosis factor α [TNFα], infterleukin-1β [IL-1β]), angiotensin II, transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) and parathyroid hormone (PTH),[40][41] although a detailed mechanistic understanding of these regulatory pathways are not yet known. Hyperglycemia and hypoxia are also known to increase OPN expression.[40][42][43]

Function edit

Apoptosis edit

OPN is an important anti-apoptotic factor in many circumstances. OPN blocks the activation-induced cell death of macrophages and T cells as well as fibroblasts and endothelial cells exposed to harmful stimuli.[44][45] OPN prevents non-programmed cell death in inflammatory colitis.[46]

Biomineralization edit

OPN belongs to a family of secreted acidic proteins (SIBLINGs, Small Integrin Binding LIgand N-Glycosylated proteins) whose members have an abundance of negatively charged amino acids such as Asp and Glu.[47] OPN also has a large number of consensus sequence sites for post-translational phosphorylation of Ser residues to form phosphoserine, providing additional negative charge.[48] Contiguous stretches of high negative charge in OPN have been identified and named the polyAsp motif (poly-aspartic acid) and the ASARM motif (acidic serine- and aspartate-rich motif), with the latter sequence having multiple phosphorylation sites.[49][50][51][52] This overall negative charge of OPN, along with its specific acidic motifs and the fact that OPN is an intrinsically disordered protein[53][6] allowing for open and flexible structures, permit OPN to bind strongly to calcium atoms available at crystal surfaces in various biominerals.[52][54][55] Such binding of OPN to various types of calcium-based biominerals ‒ such as calcium-phosphate mineral in bones and teeth,[56] calcium-carbonate mineral in inner ear otoconia[57] and avian eggshells,[58] and calcium-oxalate mineral in kidney stones[59][60][61] – acts as a mineralization inhibitor by stabilizing transient mineral precursor phases and by binding directly to crystal surfaces, all of which regulate crystal growth.[62][63][64]

OPN is a substrate protein for a number of enzymes whose actions may modulate the mineralization-inhibiting function of OPN. PHEX (phosphate-regulating endopeptidase homolog X-linked) is one such enzyme, which extensively degrades OPN, and whose inactivating gene mutations (in X-linked hypophosphatemia, XLH) lead to altered processing of OPN such that inhibitory OPN cannot be degraded and accumulates in the bone (and tooth) extracellular matrix, contributing locally to the osteomalacia (soft hypomineralized bones, and odontomalacia - soft teeth) characteristic of XLH.[65][66][12] A relationship describing local, physiologic double-negative (inhibiting inhibitors) regulation of mineralization involving OPN has been termed the Stenciling Principle of mineralization, whereby enzyme-substrate pairs imprint mineralization patterns into the extracellular matrix (most notably described for bone) by degrading mineralization inhibitors (e.g. TNAP enzyme degrading pyrophosphate inhibition, and PHEX enzyme degrading osteopontin inhibition).[67][64] In relation to mineralization diseases, the Stenciling Principle is particularly relevant to the osteomalacia and odontomalacia observed in hypophosphatasia and X-linked hypophosphatemia.

Along with its role in the regulation of normal mineralization within the extracellular matrices of bones and teeth,[68] OPN is also upregulated at sites of pathologic, ectopic calcification[69][70] – such as for example, in urolithiasis[59][61] and vascular calcification[71][69] ‒ presumably at least in part to inhibit debilitating mineralization in these soft tissues.

Bone remodeling edit

Osteopontin has been implicated as an important factor in bone remodeling.[72] Specifically, OPN anchors osteoclasts to the surface of bones where it is immobilized by its mineral-binding properties allowing subsequent usage of its RGD motif for osteoclast integrin binding for cell attachment and migration.[15] OPN at bone surfaces is located in a thin organic layer, the so-called lamina limitans.[73] The organic part of bone is about 20% of the dry weight, and counts in, other than osteopontin, collagen type I, osteocalcin, osteonectin, and alkaline phosphatase. Collagen type I counts for 90% of the protein mass. The inorganic part of bone is the mineral hydroxyapatite, Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2. Loss of bone may lead to osteoporosis, as the bone is depleted for calcium if this is not supplied in the diet.

OPN serves to initiate the process by which osteoclasts develop their ruffled borders to begin bone resorption. OPN contains and RGD integrin-binding motif

Cell activation edit

Activated T cells are promoted by IL-12 to differentiate towards the Th1 type, producing cytokines including IL-12 and IFNγ. OPN inhibits production of the Th2 cytokine IL-10, which leads to enhanced Th1 response. OPN influences cell-mediated immunity and has Th1 cytokine functions. It enhances B cell immunoglobulin production and proliferation.[7] OPN also induces mast cell degranulation.[74] IgE-mediated anaphylaxis is significantly reduced in OPN knock-out mice compared to wild-type mice. The role of OPN in activation of macrophages has also been implicated in a cancer since OPN-producing tumors were able to induce macrophage activation compared to OPN-deficient tumors.[75]

Chemotaxis edit

OPN plays an important role in neutrophil recruitment in alcoholic liver disease.[16][76] OPN is important for the migration of neutrophil in vitro.[77] In addition, OPN recruits inflammatory cells to arthritis joints in the collagen-induced arthritis model of rheumatoid arthritis.[78][79] A recent in vitro study in 2008 has found that OPN plays a role in mast cell migration.[74] Here OPN knock-out mast cells were cultured and they observed a decreased level of chemotaxis in these cells compared to wildtype mast cells. OPN was also found to act as a macrophage chemotactic factor.[80] In rhesus monkey, OPN prevents macrophages from leaving the accumulation site in brains, indicating an increased level of chemotaxis.

Immune system edit

OPN binds to several integrin receptors including α4β1, α9β1, and α9β4 expressed by leukocytes. These receptors have been well-established to function in cell adhesion, migration, and survival in these cells.

Osteopontin (OPN) is expressed in a range of immune cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, microglia and T and B cells, with varying kinetics. OPN is reported to act as an immune modulator in a variety of manners.[7] Firstly, it has chemotactic properties, which promote cell recruitment to inflammatory sites. It also functions as an adhesion protein, involved in cell attachment and wound healing. In addition, OPN mediates cell activation and cytokine production, as well as promoting cell survival by regulating apoptosis.[7] The following examples are found.[7]

Clinical significance edit

The fact that OPN interacts with multiple cell surface receptors that are ubiquitously expressed makes it an active player in many physiological and pathological processes including wound healing, bone turnover, tumorigenesis, inflammation, ischemia, and immune responses. Manipulation of plasma (or local) OPN levels may be useful in the treatment of autoimmune diseases, cancer metastasis, bone (and tooth) mineralization diseases, osteoporosis, and some forms of stress.[7]

Autoimmune diseases edit

OPN has been implicated in pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. OPN-R, the thrombin-cleaved form of OPN, is elevated in rheumatoid arthritis–affected joints. However, the role of OPN in rheumatoid arthritis is still unclear. One group found that OPN knock-out mice were protected against arthritis.[81] while others were not able to reproduce this observation.[82]

OPN has been found to play a role in other autoimmune diseases including autoimmune hepatitis, allergic airway disease, and multiple sclerosis.[83]

Allergy and asthma edit

Osteopontin has recently been associated with allergic inflammation and asthma. Expression of Opn is significantly increased in lung epithelial and subepithelial cells of asthmatic patients in comparison to healthy subjects.[84] Opn expression is also upregulated in lungs of mice with allergic airway inflammation.[84] The secreted form of Opn (Opn-s) plays a proinflammatory role during allergen sensitization (OVA/Alum), as neutralization of Opn-s during that phase results in significantly milder allergic airway inflammation.[84] In contrast, neutralization of Opn-s during antigenic challenge exacerbates allergic airway disease.[84] These effects of Opn-s are mainly mediated by the regulation of Th2-suppressing plasmacytoid dendritic cells (DCs) during primary sensitization and Th2-promoting conventional DCs during secondary antigenic challenge.[84] OPN deficiency was also reported to protect against remodeling and bronchial hyperresponsiveness (BHR), again using a chronic allergen-challenge model of airway remodeling.[85] Furthermore, it was recently demonstrated that OPN expression is upregulated in human asthma, is associated with remodeling changes and its subepithelial expression correlates to disease severity.[86] OPN has also been reported to be increased in the sputum supernatant of smoking asthmatics,[87] as well as the BALF and bronchial tissue of smoking controls and asthmatics.[88]

Colitis edit

Opn is up-regulated in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).[89] Opn expression is highly up-regulated in intestinal immune and non-immune cells and in the plasma of patients with Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), as well as in the colon and plasma of mice with experimental colitis.[89][90][91] Increased plasma Opn levels are related to the severity of CD inflammation, and certain Opn gene (Spp1) haplotypes are modifiers of CD susceptibility. Opn has also a proinflammatory role in TNBS- and dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis, which are mouse models for IBD. Opn was found highly expressed by a specific dendritic cell (DC) subset derived from murine mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) and is highly proinflammatory for colitis.[92] Dendritic cells are important for the development of intestinal inflammation in humans with IBD and in mice with experimental colitis. Opn expression by this inflammatory MLN DC subset is crucial for their pathogenic action during colitis.[92]

Cancer edit

It has been shown that OPN drives IL-17 production;[93] OPN is overexpressed in a variety of cancers, including lung cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, stomach cancer, ovarian cancer, papillary thyroid carcinoma, melanoma and pleural mesothelioma; OPN contributes both glomerulonephritis and tubulointerstitial nephritis; and OPN is found in atheromatous plaques within arteries. Thus, manipulation of plasma OPN levels may be useful in the treatment of autoimmune diseases, cancer metastasis, osteoporosis and some forms of stress.[7]

Osteopontin is implicated in PDAC (pancreatic adenocarcinoma) disease progression.[94] It is expressed as one of three splice variants in PDAC, with osteopontin-a expressed in nearly all PDAC, osteopontin-b expression correlating with survival, and osteopontin-c correlating with metastatic disease . Because PDAC secretes alternatively spliced forms of osteopontin, it shows potential for tumor- and disease stage-specific targeting. Although the exact mechanisms of osteopontin signaling in PDAC are unknown, it binds to CD44 and integrins to trigger processes such as tumor progression and complement inhibition. Osteopontin also drives metastasis by triggering the release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and matrix metalloprotease (MMP), which is inhibited by knocking down osteopontin. This process is also stimulated by nicotine, which is the proposed mechanism by which smokers experience elevated PC risk. Osteopontin is being explored as a marker for PC. It was found to perform better than CA19.9 in discerning IPMN [80] and resectable PDAC from pancreatitis . Antiosteopontin antibodies are being developed, including hu1A12, which inhibited metastasis in an in vivo study and also when hybridized with the anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab . At least one clinical trial is exploring the use of osteopontin as a marker of intratumoral hypoxia. However, this marker remains relatively unexplored.[95]

Osteopontin is also implicated in excessive scar-formation and a gel has been developed to inhibit its effect.[96]

AOM1, an anti-osteopontin monoclonal antibody drug developed by Pfizer, Inc. to inhibit osteopontin, showed promise at preventing progression of large metastatic tumors in mouse models of NSCLC.[97][98]

Even though Opn promotes metastasis and can be used as a cancer biomarker, latest studies described novel protecting functions of the molecule on innate cell populations during tumor development. Particularly, maintenance of a pool of natural killer (NK) cells with optimal immune function is crucial for host defense against cancerous tumor formation. A study in PNAS describes iOpn is an essential molecular component responsible for maintenance of functional NK cell expansion. Absence of iOPN results in failure to maintain normal NK cellularity and increased cell death following stimulation by cytokine IL-15. OPN-deficient NK cells fail to successfully navigate the contraction phase of the immune response, resulting in impaired expansion of long-lived NK cells and defective responses to tumor cells.[99]In addition, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) protect from melanoma, and this effect is mediated by type I IFNs.[100] A study in JCB showed that a specific fragment (SLAYGLR) of the Opn protein can render pDCs more “fit” to protect from melanoma development. This was achieved by activation of a novel α4 integrin/IFN-β axis which is MyD88-independent and operates via a PI3K/mTOR/IRF3 pathway.[101]

Heart failure edit

Osteopontin is minimally expressed under normal conditions, but accumulates quickly as heart function declines.[102][103] Specifically, it plays a central role in the remodeling response to myocardial infarction, and is dramatically upregulated in hypertrophic (HCM) and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM).[103] Once abundant, it stimulates a wide range of physiological changes in the myocardium, including angiogenesis, local production of cytokines, differentiation of myofibroblasts, increased deposition of extracellular matrix, and hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes. Taken together, these processes remodel the structure of the heart, in effect reducing its ability to function normally, and increasing risk for heart failure.[104][105]

Parkinson's disease edit

OPN plays a role in oxidative and nitrosative stress, apoptosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, and excitotoxicity, which are also involved in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. PD patients serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of OPN were studied, it shows that OPN levels in the body fluid is elevated in PD patients.[106]

Muscle disease and injury edit

Evidence is accumulating that suggests that osteopontin plays a number of roles in diseases of skeletal muscle, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Osteopontin has been described as a component of the inflammatory environment of dystrophic and injured muscles,[28][107][108][109] and has also been shown to increase scarring of diaphragm muscles of aged dystrophic mice.[110] A recent study has identified osteopontin as a determinant of disease severity in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.[111] This study found that a mutation in the osteopontin gene promoter, known to cause low levels of osteopontin expression, is associated with a decrease in age to loss of ambulation and muscle strength in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Hip osteoarthritis edit

An increase in Plasma OPN levels has been observed in patients with idiopathic hip OA. Furthermore, a correlation between OPN plasma levels and the severity of the disease has been noted.[112]

Fertilized egg implantation edit

OPN is expressed in endometrial cells during implantation. Due to the production of progesterone by the ovaries, OPN is up-regulated immensely to aid in this process. The endometrium must undergo decidualization, the process in which the endometrium undergoes changes to prepare for implantation, which will lead to the attachment of the embryo. The endometrium houses stromal cells that will differentiate to produce an optimal environment for the embryo to attach (decidualization). OPN is a vital protein for stromal cell proliferation and differentiation as well as it binds to the receptor αvβ3 to assist with adhesion. OPN along with decidualization ultimately encourages the successful implantation of the early embryo. An OPN gene knock-out results in attachment instability at the maternal-fetal interface.[113][114]

References edit

Further reading edit

- Fujisawa R (March 2002). "[Recent advances in research on bone matrix proteins]". Nihon Rinsho. Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine. 60. 60 (Suppl 3): 72–78. PMID 11979972.

- Denhardt DT, Mistretta D, Chambers AF, Krishna S, Porter JF, Raghuram S, Rittling SR (2003). "Transcriptional regulation of osteopontin and the metastatic phenotype: evidence for a Ras-activated enhancer in the human OPN promoter". Clinical & Experimental Metastasis. 20 (1): 77–84. doi:10.1023/A:1022550721404. PMID 12650610. S2CID 20286402.

- Yeatman TJ, Chambers AF (2003). "Osteopontin and colon cancer progression". Clinical & Experimental Metastasis. 20 (1): 85–90. doi:10.1023/A:1022502805474. PMID 12650611. S2CID 25253392.

- O'Regan A (December 2003). "The role of osteopontin in lung disease". Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 14 (6): 479–488. doi:10.1016/S1359-6101(03)00055-8. PMID 14563350.

- Wai PY, Kuo PC (October 2004). "The role of Osteopontin in tumor metastasis". The Journal of Surgical Research. 121 (2): 228–241. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2004.03.028. PMID 15501463.

- Konno S, Hizawa N, Nishimura M, Huang SK (December 2006). "Osteopontin: a potential biomarker for successful bee venom immunotherapy and a potential molecule for inhibiting IgE-mediated allergic responses". Allergology International. 55 (4): 355–359. doi:10.2332/allergolint.55.355. PMID 17130676.

- Rodrigues LR, Teixeira JA, Schmitt FL, Paulsson M, Lindmark-Mänsson H (June 2007). "The role of osteopontin in tumor progression and metastasis in breast cancer". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 16 (6): 1087–1097. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1008. hdl:1822/7274. PMID 17548669.

- Ramaiah SK, Rittling S (August 2007). "Role of osteopontin in regulating hepatic inflammatory responses and toxic liver injury". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 3 (4): 519–526. doi:10.1517/17425225.3.4.519. PMID 17696803.

External links edit

- Osteopontin at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P10451 (Osteopontin) at the PDBe-KB.