Quinary /ˈkwaɪnəri/[1] (base 5 or pental[2][3][4]) is a numeral system with five as the base. A possible origination of a quinary system is that there are five digits on either hand.

In the quinary place system, five numerals, from 0 to 4, are used to represent any real number. According to this method, five is written as 10, twenty-five is written as 100, and sixty is written as 220.

As five is a prime number, only the reciprocals of the powers of five terminate, although its location between two highly composite numbers (4 and 6) guarantees that many recurring fractions have relatively short periods.

Today, the main usage of quinary is as a biquinary system, which is decimal using five as a sub-base. Another example of a sub-base system is sexagesimal (base sixty), which used ten as a sub-base.

Each quinary digit can hold (approx. 2.32) bits of information.

Comparison to other radices edit

| × | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 20 |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 20 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 13 | 20 | 22 | 24 | 31 | 33 | 40 |

| 3 | 3 | 11 | 14 | 22 | 30 | 33 | 41 | 44 | 102 | 110 |

| 4 | 4 | 13 | 22 | 31 | 40 | 44 | 103 | 112 | 121 | 130 |

| 10 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 100 | 110 | 120 | 130 | 140 | 200 |

| 11 | 11 | 22 | 33 | 44 | 110 | 121 | 132 | 143 | 204 | 220 |

| 12 | 12 | 24 | 41 | 103 | 120 | 132 | 144 | 211 | 223 | 240 |

| 13 | 13 | 31 | 44 | 112 | 130 | 143 | 211 | 224 | 242 | 310 |

| 14 | 14 | 33 | 102 | 121 | 140 | 204 | 223 | 242 | 311 | 330 |

| 20 | 20 | 40 | 110 | 130 | 200 | 220 | 240 | 310 | 330 | 400 |

| Quinary | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binary | 0 | 1 | 10 | 11 | 100 | 101 | 110 | 111 | 1000 | 1001 | 1010 | 1011 | 1100 |

| Decimal | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Quinary | 23 | 24 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 100 |

| Binary | 1101 | 1110 | 1111 | 10000 | 10001 | 10010 | 10011 | 10100 | 10101 | 10110 | 10111 | 11000 | 11001 |

| Decimal | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| Decimal (periodic part) | Quinary (periodic part) | Binary (periodic part) |

| 1/2 = 0.5 | 1/2 = 0.2 | 1/10 = 0.1 |

| 1/3 = 0.3 | 1/3 = 0.13 | 1/11 = 0.01 |

| 1/4 = 0.25 | 1/4 = 0.1 | 1/100 = 0.01 |

| 1/5 = 0.2 | 1/10 = 0.1 | 1/101 = 0.0011 |

| 1/6 = 0.16 | 1/11 = 0.04 | 1/110 = 0.010 |

| 1/7 = 0.142857 | 1/12 = 0.032412 | 1/111 = 0.001 |

| 1/8 = 0.125 | 1/13 = 0.03 | 1/1000 = 0.001 |

| 1/9 = 0.1 | 1/14 = 0.023421 | 1/1001 = 0.000111 |

| 1/10 = 0.1 | 1/20 = 0.02 | 1/1010 = 0.00011 |

| 1/11 = 0.09 | 1/21 = 0.02114 | 1/1011 = 0.0001011101 |

| 1/12 = 0.083 | 1/22 = 0.02 | 1/1100 = 0.0001 |

| 1/13 = 0.076923 | 1/23 = 0.0143 | 1/1101 = 0.000100111011 |

| 1/14 = 0.0714285 | 1/24 = 0.013431 | 1/1110 = 0.0001 |

| 1/15 = 0.06 | 1/30 = 0.013 | 1/1111 = 0.0001 |

| 1/16 = 0.0625 | 1/31 = 0.0124 | 1/10000 = 0.0001 |

| 1/17 = 0.0588235294117647 | 1/32 = 0.0121340243231042 | 1/10001 = 0.00001111 |

| 1/18 = 0.05 | 1/33 = 0.011433 | 1/10010 = 0.0000111 |

| 1/19 = 0.052631578947368421 | 1/34 = 0.011242141 | 1/10011 = 0.000011010111100101 |

| 1/20 = 0.05 | 1/40 = 0.01 | 1/10100 = 0.000011 |

| 1/21 = 0.047619 | 1/41 = 0.010434 | 1/10101 = 0.000011 |

| 1/22 = 0.045 | 1/42 = 0.01032 | 1/10110 = 0.00001011101 |

| 1/23 = 0.0434782608695652173913 | 1/43 = 0.0102041332143424031123 | 1/10111 = 0.00001011001 |

| 1/24 = 0.0416 | 1/44 = 0.01 | 1/11000 = 0.00001 |

| 1/25 = 0.04 | 1/100 = 0.01 | 1/11001 = 0.00001010001111010111 |

Usage edit

Many languages[5] use quinary number systems, including Gumatj, Nunggubuyu,[6] Kuurn Kopan Noot,[7] Luiseño,[8] and Saraveca. Gumatj has been reported to be a true "5–25" language, in which 25 is the higher group of 5. The Gumatj numerals are shown below:[6]

| Number | Base 5 | Numeral |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | wanggany |

| 2 | 2 | marrma |

| 3 | 3 | lurrkun |

| 4 | 4 | dambumiriw |

| 5 | 10 | wanggany rulu |

| 10 | 20 | marrma rulu |

| 15 | 30 | lurrkun rulu |

| 20 | 40 | dambumiriw rulu |

| 25 | 100 | dambumirri rulu |

| 50 | 200 | marrma dambumirri rulu |

| 75 | 300 | lurrkun dambumirri rulu |

| 100 | 400 | dambumiriw dambumirri rulu |

| 125 | 1000 | dambumirri dambumirri rulu |

| 625 | 10000 | dambumirri dambumirri dambumirri rulu |

However, Harald Hammarström reports that "one would not usually use exact numbers for counting this high in this language and there is a certain likelihood that the system was extended this high only at the time of elicitation with one single speaker," pointing to the Biwat language as a similar case (previously attested as 5-20, but with one speaker recorded as making an innovation to turn it 5-25).[5]

Biquinary edit

A decimal system with two and five as a sub-bases is called biquinary and is found in Wolof and Khmer. Roman numerals are an early biquinary system. The numbers 1, 5, 10, and 50 are written as I, V, X, and L respectively. Seven is VII, and seventy is LXX. The full list of symbols is:

| Roman | I | V | X | L | C | D | M |

| Decimal | 1 | 5 | 10 | 50 | 100 | 500 | 1000 |

Note that these are not positional number systems. In theory, a number such as 73 could be written as IIIXXL (without ambiguity) and as LXXIII. To extend Roman numerals to beyond thousands, a vinculum (horizontal overline) was added, multiplying the letter value by a thousand, e.g. overlined M̅ was one million. There is also no sign for zero. But with the introduction of inversions like IV and IX, it was necessary to keep the order from most to least significant.

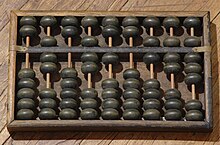

Many versions of the abacus, such as the suanpan and soroban, use a biquinary system to simulate a decimal system for ease of calculation. Urnfield culture numerals and some tally mark systems are also biquinary. Units of currencies are commonly partially or wholly biquinary.

Bi-quinary coded decimal is a variant of biquinary that was used on a number of early computers including Colossus and the IBM 650 to represent decimal numbers.

Quadquinary edit

A vigesimal system with four and five as a sub-bases is found in Nahuatl.[citation needed][dubious ]

Calculators and programming languages edit

Few calculators support calculations in the quinary system, except for some Sharp models (including some of the EL-500W and EL-500X series, where it is named the pental system[2][3][4]) since about 2005, as well as the open-source scientific calculator WP 34S.

Python's int() function supports conversion of numeral systems from any base to decimal. Thus, the quinary number 101 is evaluated using int('101',5) as the decimal numeral 26.[9]

See also edit

- Pentadic numerals – Runic notation for presenting numbers

- Bi-quinary coded decimal

References edit

- ^ "quinary". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.[dead link]

- ^ a b "SHARP" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-07-12. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- ^ a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-02-22. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "SHARP" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-07-12. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- ^ a b Hammarström, Harald (March 26, 2010). "Rarities in numeral systems". Rethinking Universals. Vol. 45. De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 11–60. doi:10.1515/9783110220933.11. ISBN 9783110220933. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- ^ a b Harris, John W. (December 1982). "Facts and fallacies of Aboriginal number system" (PDF). www1.aiatsis.gov.au. Work Papers of SIL-AAB. pp. 153–181. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 31, 2007. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- ^ Dawson, James (1981). Australian aborigines : the languages and customs of several tribes of aborigines in the western district of Victoria, Australia. University of Michigan. Canberra City, ACT, Australia : Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies; Atlantic Highlands, NJ : Humanities Press [distributor]. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- ^ Closs, Michael P. (1986). Native American Mathematics. ISBN 0-292-75531-7.[dead link]

- ^ Kay, Naftuli (2012-01-19). "Convert base-2 binary number string to int". Stack Overflow. Archived from the original on 24 November 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

External links edit

- Quinary Base Conversion, includes fractional part, from Math Is Fun

Media related to Quinary numeral system at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Quinary numeral system at Wikimedia Commons- Quinary-pentavigesimal and decimal calculator, uses D'ni numerals from the Myst franchise, integers only, fan-made.