The historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles, the principal historical source for the Apostolic Age, is of interest for biblical scholars and historians of Early Christianity as part of the debate over the historicity of the Bible. Historical reliability is not dependent on a source being inerrant or void of agendas since there are sources that are considered generally reliable despite having such traits (e.g. Josephus).[1]

Archaeological inscriptions and other independent sources show that Acts of the Apostles (“Acts”) contains some accurate details of 1st century society with regard to the titles of officials, administrative divisions, town assemblies, and rules of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. However, the historicity of the depiction of Paul the Apostle in Acts is contested. Acts describes Paul differently from how Paul describes himself, both factually and theologically.[2] Acts differs with Paul's letters on important issues, such as the Law, Paul's own apostleship, and his relation to the Jerusalem church.[2] Scholars generally prefer Paul's account over that in Acts.[3]: 316 [4]: 10 However, Roman historians have generally taken the basic historicity of Acts as granted.[5]

Composition edit

Narrative edit

Luke–Acts is a two-part historical account traditionally ascribed to Luke the Evangelist, who was believed to be a follower of Paul. The author of Luke–Acts noted that there were many accounts in circulation at the time of his writing, saying that these were eyewitness testimonies. He stated that he had investigated "everything from the beginning" and was editing the material into one account from the birth of Jesus to his own time. Like other historians of his time,[6][7][8][9] he defined his actions by stating that the reader can rely on the "certainty" of the facts given. However, most scholars understand Luke–Acts to be in the tradition of Hellenic historiography.[10][11][12]

Use of sources edit

It has been claimed that the author of Acts used the writings of Josephus (specifically Antiquities of the Jews) as a historical source.[13][14] The majority of scholars reject both this claim and the claim that Josephus borrowed from Acts,[15][16][17] arguing instead that Luke and Josephus drew on common traditions and historical sources.[18][19][20][21][22][23]

Several scholars[who?] have criticised the author's use of his source materials. For example, Richard Heard has written that, "in his narrative in the early part of Acts he seems to be stringing together, as best he may, a number of different stories and narratives, some of which appear, by the time they reached him, to have been seriously distorted in the telling."[24][page needed]

Textual traditions edit

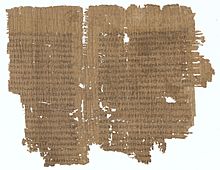

Like most New Testament books, there are significant differences among the earliest surviving manuscripts of Acts. In the case of Acts, the differences between the surviving manuscripts are especially substantial. Arguably the two earliest versions of manuscripts are the Western text-type (as represented by the Codex Bezae) and the Alexandrian text-type (as represented by the Codex Vaticanus and the Codex Sinaiticus which was not seen in Europe until 1859). The version of Acts preserved in the Western manuscripts contains about 6.2–8.5%[25] more content than the Alexandrian version of Acts (depending on the definition of a variant).[4]: 5–6

Modern scholars contend that the shorter Alexandrian text is closer to the original, and the longer Western text is the result of later insertion of additional material into the text.[4]: 5–6

A third class of manuscripts, known as the Byzantine text-type, is often considered to have developed after the Western and Alexandrian types. While differing from both of the other types, the Byzantine type has more similarity to the Alexandrian than to the Western type. The extant manuscripts of this type date from the 5th century or later; however, papyrus fragments show that this text-type may date as early as the Alexandrian or Western text-types.[26]: 45–48 The Byzantine text-type served as the basis for the 16th century Textus Receptus, produced by Erasmus, the first Greek-language printed edition of the New Testament. The Textus Receptus, in turn, served as the basis for the New Testament in the English-language King James Bible. Today, the Byzantine text-type is the subject of renewed interest as the possible original form of the text from which the Western and Alexandrian text-types were derived.[27][page needed]

Historicity edit

The debate on the historicity of Acts became most vehement between 1895 and 1915.[28] Ferdinand Christian Baur viewed it as unreliable, and mostly an effort to reconcile Gentile and Jewish forms of Christianity.[4]: 10 Adolf von Harnack in particular was known for being very critical of the accuracy of Acts, though his allegations of its inaccuracies have been described as "exaggerated hypercriticism" by some.[29] Leading scholar and archaeologist of the time period, William Mitchell Ramsay, considered Acts to be remarkably reliable as a historical document.[30] Attitudes towards the historicity of Acts have ranged widely across scholarship in different countries.[31]

According to Heidi J. Hornik and Mikeal C. Parsons, "Acts must be carefully sifted and mined for historical information."[4]: 10

Passages consistent with the historical background edit

Acts contains some accurate details of 1st century society, specifically with regard to titles of officials, administrative divisions, town assemblies, and rules of the Jewish temple in Jerusalem,[32] including:

- Inscriptions confirm that the city authorities in Thessalonica in the 1st century were called politarchs (Acts 17:6–8)

- According to inscriptions, grammateus is the correct title for the chief magistrate in Ephesus (Acts 19:35)

- Marcus Antonius Felix and Porcius Festus are correctly called procurators of Judea

- The passing remark of the expulsion of the Jews from Rome by Claudius (Acts 18:2) is independently attested by Suetonius in Claudius 25 from The Twelve Caesars, Cassius Dio in Roman History and fifth-century Christian author Paulus Orosius in his History Against the Pagans.[33][34]

- Acts correctly refers to Cornelius as centurion and to Claudius Lysias as a tribune (Acts 21:31 and Acts 23:26)

- The title proconsul (anthypathos) is correctly used for the governors of the two senatorial provinces named in Acts (Acts 13:7–8 and Acts 18:12)

- Lucius Junius Gallio Annaeanus's tenure as proconsul of Achaea is confirmed by the Delphi Inscription (Acts 18:12-17)

- Inscriptions speak about the prohibition against the Gentiles in the inner areas of the Temple (as in Acts 21:27–36); see also Court of the Gentiles

- The function of town assemblies in the operation of a city's business is described accurately in Acts 19:29–41

- Roman soldiers were permanently stationed in the tower of Antonia with the responsibility of watching for and suppressing any disturbances at the festivals of the Jews; to reach the affected area they would have to come down a flight of steps into temple precincts, as noted by Acts 21:31–37

Charles H. Talbert concludes that the historical inaccuracies within Acts "are few and insignificant compared to the overwhelming congruence of Acts and its time [until AD 64] and place [Palestine and the wider Roman Empire]".[32] Talbert cautions nevertheless that "an exact description of the milieu does not prove the historicity of the event narrated".[35]

Whilst treating its description of the history of the early church skeptically, critical scholars such as Gerd Lüdemann, Alexander Wedderburn, Hans Conzelmann, and Martin Hengel still view Acts as containing valuable historically accurate accounts of the earliest Christians.

Lüdemann acknowledges the historicity of Christ's post-resurrection appearances,[36] the names of the early disciples,[37] women disciples,[38] and Judas Iscariot.[39] Wedderburn says the disciples indisputably believed Christ was truly raised.[40] Conzelmann dismisses an alleged contradiction between Acts 13:31 and Acts 1:3.[41] Hengel believes Acts was written early[42] by Luke as a partial eyewitness,[43] praising Luke's knowledge of Palestine,[44] and of Jewish customs in Acts 1:12.[45] With regard to Acts 1:15–26, Lüdemann is skeptical with regard to the appointment of Matthias, but not with regard to his historical existence.[46] Wedderburn rejects the theory that denies the historicity of the disciples,[47][48] Conzelmann considers the upper room meeting a historical event Luke knew from tradition,[49] and Hengel considers ‘the Field of Blood’ to be an authentic historical name.[50]

Concerning Acts 2, Lüdemann considers the Pentecost gathering as very possible,[51] and the apostolic instruction to be historically credible.[52] Wedderburn acknowledges the possibility of a ‘mass ecstatic experience’,[53] and notes it is difficult to explain why early Christians later adopted this Jewish festival if there had not been an original Pentecost event as described in Acts.[54] He also holds the description of the early community in Acts 2 to be reliable.[55][56]

Lüdemann views Acts 3:1–4:31 as historical.[57] Wedderburn notes what he sees as features of an idealized description,[58] but nevertheless cautions against dismissing the record as unhistorical.[59] Hengel likewise insists that Luke described genuine historical events, even if he has idealized them.[60][61]

Wedderburn maintains the historicity of communal ownership among the early followers of Christ (Acts 4:32–37).[62] Conzelmann, though sceptical, believes Luke took his account of Acts 6:1–15 from a written record;[63] more positively, Wedderburn defends the historicity of the account against scepticism.[64] Lüdemann considers the account to have a historical basis.[65]

Passages of disputed historical accuracy edit

Acts 2:41 and 4:4 – Peter's addresses edit

Acts 4:4 speaks of Peter addressing an audience, resulting in the number of Christian converts rising to 5,000 people. A Professor of the New Testament Robert M. Grant says "Luke evidently regarded himself as a historian, but many questions can be raised in regard to the reliability of his history [...] His ‘statistics’ are impossible; Peter could not have addressed three thousand hearers [e.g. in Acts 2:41] without a microphone, and since the population of Jerusalem was about 25–30,000, Christians cannot have numbered five thousand [e.g. Acts 4:4]."[66] However, as Professor I. Howard Marshall shows, the believers could have possibly come from other countries (see Acts 2: 9-10). In regards to being heard, recent history suggests that a crowd of thousands can be addressed; for instance, Benjamin Franklin's account about George Whitefield notes that crowds of thousands could be addressed by a single speaker without the aid of technological implements. [67]

Acts 5:33–39: Theudas edit

Acts 5:33–39 gives an account of speech by the 1st century Pharisee Gamaliel (d. ~50ad), in which he refers to two first century movements. One of these was led by Theudas.[68] Afterwards another was led by Judas the Galilean.[69] Josephus placed Judas at the Census of Quirinius of the year 6 and Theudas under the procurator Fadus[70] in 44–46. Assuming Acts refers to the same Theudas as Josephus, two problems emerge. First, the order of Judas and Theudas is reversed in Acts 5. Second, Theudas's movement may come after the time when Gamaliel is speaking. It is possible that Theudas in Josephus is not the same one as in Acts, or that it is Josephus who has his dates confused.[71] The 3rd-century writer Origen referred to a Theudas active before the birth of Jesus,[72] although it is possible that this simply draws on the account in Acts.

Acts 10:1: Roman troops in Caesarea edit

Acts 10:1 speaks of a Roman Centurion called Cornelius belonging to the "Italian regiment" and stationed in Caesarea about 37 AD. Robert M. Grant claims that during the reign of Herod Agrippa, 41–44, no Roman troops were stationed in his territory.[73] Wedderburn likewise finds the narrative "historically suspect",[74] and in view of the lack of inscriptional and literary evidence corroborating Acts, historian de Blois suggests that the unit either did not exist or was a later unit which the author of Acts projected to an earlier time.[75]

Noting that the 'Italian regiment' is generally identified as cohors II Italica civium Romanorum, a unit whose presence in Judea is attested no earlier than AD 69,[76] historian E. Mary Smallwood observes that the events described from Acts 9:32 to chapter 11 may not be in chronological order with the rest of the chapter but actually take place after Agrippa's death in chapter 12, and that the "Italian regiment" may have been introduced to Caesarea as early as AD 44.[77] Wedderburn notes this suggestion of chronological re-arrangement, along with the suggestion that Cornelius lived in Caesarea away from his unit.[78] Historians such as Bond,[79] Speidel,[80] and Saddington,[81] see no difficulty in the record of Acts 10:1.

Acts 15: The Council of Jerusalem edit

The description of the 'Apostolic Council' in Acts 15, generally considered the same event described in Galatians 2,[82] is considered by some scholars to be contradictory to the Galatians account.[83] The historicity of Luke's account has been challenged,[84][85][86] and was rejected completely by some scholars in the mid to late 20th century.[87] However, more recent scholarship inclines towards treating the Jerusalem Council and its rulings as a historical event,[88] though this is sometimes expressed with caution.[89]

Acts 15:16–18: James' speech edit

In Acts 15:16–18, James, the leader of the Christian Jews in Jerusalem, gives a speech where he quotes scriptures from the Greek Septuagint (Amos 9:11–12). Some believe this is incongruous with the portrait of James as a Jew, who would presumably have spoken Aramaic rather than Greek. For instance, Richard Pervo notes: "The scriptural citation strongly differs from the MT which has nothing to do with the inclusion of gentiles. This is the vital element in the citation and rules out the possibility that the historical James (who would not have cited the LXX) utilized the passage."[90]

A possible explanation is that the Septuagint translation better made James's point about the inclusion of gentiles as the people of God.[91]

Acts 21:38: The sicarii and the Egyptian edit

In Acts 21:38, a Roman asks Paul if he was 'the Egyptian' who led a band of 'sicarii' (literally: 'dagger-men') into the desert. In both The Jewish Wars[92] and Antiquities of the Jews,[93] Josephus talks about Jewish nationalist rebels called sicarii directly prior to talking about the Egyptian leading some followers to the Mount of Olives. Richard Pervo believes that this demonstrates that Luke used Josephus as a source and mistakenly thought that the sicarii were followers of The Egyptian.[94][95]

Other sources for early Church history edit

Two early sources that mention the origins of Christianity are the Antiquities of the Jews by the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus, and the Church History of Eusebius. Josephus and Luke-Acts are thought to be approximately contemporaneous, around AD 90, and Eusebius wrote some two and a quarter centuries later.

More indirect evidence can be obtained from other New Testament writings, early Christian apocrypha, and non-Christian sources such as the correspondence between Pliny and Trajan (AD 112). Even Christian pseudepigrapha sometimes give potential insights into how early Christian communities formed and functioned, the kind of issues they faced and what sort of beliefs they developed.[citation needed]

See also edit

References edit

Further reading edit

- I. Howard Marshall. Luke: Historian and Theologian. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press 1970.

- F.F. Bruce. The Speeches in the Acts of the Apostles. Archived 2012-05-31 at the Wayback Machine London: The Tyndale Press, 1942.

- Helmut Koester. Ancient Christian Gospels. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Trinity Press International, 1999.

- Colin J. Hemer. The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1989.

- J. Wenham, "The Identification of Luke", Evangelical Quarterly 63 (1991), 3–44

External links edit

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. See section titled Objections against the authenticity.

- Jewish Encyclopedia: New Testament: The Acts of the Apostles