John the Evangelist[a] is the name traditionally given to the author of the Gospel of John. Christians have traditionally identified him with John the Apostle, John of Patmos, and John the Presbyter,[2] although this has been disputed by most modern scholars.[3]

John the Evangelist | |

|---|---|

Detail from a window in the parish church of SS Mary and Lambert, Stonham Aspal, Suffolk, with stained glass representing St John the Evangelist | |

| Evangelist, Apostle, Theologian | |

| Born | Between c. AD 6–9 |

| Died | c. AD 100[1] |

| Venerated in | |

| Feast | 27 December (Western Christianity); 8 May and 26 September (Repose) (Eastern Orthodox Church) |

| Attributes | Eagle, Chalice, Scrolls |

| Major works |

|

Identity edit

The exact identity of John – and the extent to which his identification with John the Apostle, John of Patmos and John the Presbyter is historical – is disputed between Christian tradition and scholars.

The Gospel of John refers to an otherwise unnamed "disciple whom Jesus loved", who "bore witness to and wrote" the Gospel's message.[5] The author of the Gospel of John seemed interested in maintaining the internal anonymity of the author's identity, although interpreting the Gospel in the light of the Synoptic Gospels and considering that the author names (and therefore is not claiming to be) Peter, and that James was martyred as early as AD 44,[6] Christian tradition has widely believed that the author was the Apostle John, though modern scholars believe the work to be pseudepigrapha.[7]

Christian tradition says that John the Evangelist was John the Apostle. John, Peter and James the Just were the three pillars of the Jerusalem church after Jesus' death.[8] He was one of the original twelve apostles and is thought to be the only one to escape martyrdom. It had been believed that he was exiled (around AD 95) to the Aegean island of Patmos, where he wrote the Book of Revelation. However, some attribute the authorship of Revelation to another man, called John the Presbyter, or to other writers of the late first century AD.[9] Bauckham argues that the early Christians identified John the Evangelist with John the Presbyter.[10]

Authorship of the Johannine works edit

The authorship of the Johannine works has been debated by scholars since at least the 2nd century AD.[11] The main debate centers on who authored the writings, and which of the writings, if any, can be ascribed to a common author.

Eastern Orthodox tradition attributes all of the Johannine books to John the Apostle.[2]

In the 6th century, the Decretum Gelasianum argued that Second and Third Epistle of John have a separate author known as "John, a priest" (see John the Presbyter).[b] Historical critics, like H.P.V. Nunn,[12] as well as non-Christians Reza Aslan[13] and Bart Ehrman,[14] reject the view that John the Apostle authored any of these works.

Most modern scholars believe that the apostle John wrote none of these works,[15][16] although some, such as J.A.T. Robinson, F. F. Bruce, Leon Morris, and Martin Hengel,[17] hold the apostle to be behind at least some, in particular the gospel.[18][19]

There may have been a single author for the gospel and the three epistles.[2] Some scholars conclude the author of the epistles was different from that of the gospel, although all four works originated from the same community.[20] The gospel and epistles traditionally and plausibly came from Ephesus, c. 90–110, although some scholars argue for an origin in Syria.[21]

In the case of the Book Revelation, most modern scholars agree that it was written by a separate author, John of Patmos, c. 95 with some parts possibly dating to Nero's reign in the early 60s.[22][23][24][2][15][16][3]

Feast day edit

The feast day of Saint John in the Catholic Church, Anglican Communion, and the Lutheran Calendar, is on 27 December, the third day of Christmastide.[25] In the Tridentine calendar he was commemorated also on each of the following days up to and including 3 January, the Octave of the 27 December feast. This Octave was abolished by Pope Pius XII in 1955.[26] The traditional liturgical color is white.

Freemasons celebrate this feast day, dating back to the 18th century when the Feast Day was used for the installation of Grand Masters.[27]

In art edit

John is traditionally depicted in one of two distinct ways: either as an aged man with a white or gray beard, or alternatively as a beardless youth.[28][29] The first way of depicting him was more common in Byzantine art, where it was possibly influenced by antique depictions of Socrates;[30] the second was more common in the art of Medieval Western Europe and can be dated back as far as 4th-century Rome.[29]

In medieval works of painting, sculpture and literature, Saint John is often presented in an androgynous or feminized manner.[31] Historians have related such portrayals to the circumstances of the believers for whom they were intended.[32] For instance, John's feminine features are argued to have helped to make him more relatable to women.[33] Likewise, Sarah McNamer argues that because of John's androgynous status, he could function as an 'image of a third or mixed gender'[34] and 'a crucial figure with whom to identify'[35] for male believers who sought to cultivate an attitude of affective piety, a highly emotional style of devotion that, in late-medieval culture, was thought to be poorly compatible with masculinity.[36]

Legends from the "Acts of John" contributed much to medieval iconography; it is the source of the idea that John became an apostle at a young age.[29] One of John's familiar attributes is the chalice, often with a snake emerging from it.[37] According to one legend from the Acts of John,[38] John was challenged to drink a cup of poison to demonstrate the power of his faith, and thanks to God's aid the poison was rendered harmless.[37][39] The chalice can also be interpreted with reference to the Last Supper, or to the words of Christ to John and James: "My chalice indeed you shall drink."[40][41] According to the 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia, some authorities believe that this symbol was not adopted until the 13th century.[41] There was also a legend that John was at some stage boiled in oil and miraculously preserved.[42] Another common attribute is a book or a scroll, in reference to his writings.[37] John the Evangelist is symbolically represented by an eagle, one of the creatures envisioned by Ezekiel (1:10)[43] and in the Book of Revelation (4:7).[44][41]

Gallery edit

- John the Evangelist

- St. John the Evangelist by Joan de Joanes (1507–1579), oil on panel

- Saint John the Evangelist by Domenichino (1621–29)

- Saint John the Evangelist on Patmos, 1490

- Piero di Cosimo, Saint John the Evangelist, oil on panel, 1504–6, Honolulu Museum of Art

- The Vision of Saint John (1608–1614), by El Greco

- Saints John and Bartholomew, by Dosso Dossi

- Stained glass window in St. Aidan's Cathedral, Ireland

- Saint John and the eagle by Vladimir Borovikovsky in Kazan Cathedral, Saint Petersburg

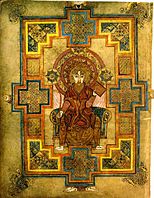

- A portrait from the Book of Kells, c. 800

- Saint John and the cup by El Greco

- Statue of John the Evangelist outside St. John's Seminary, Boston

- St John the Evangelist depicted in a 14th-century manuscript in the Flemish style

- St John the Evangelist, by Francisco Pacheco (1608, Museo del Prado)

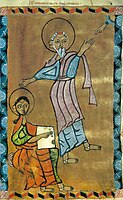

- Prochorus and St John depicted in Xoranasat's gospel manuscript in 1224. Armenian manuscript.

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ Greek: Ἰωάννης, translit. Iōánnēs; Imperial Aramaic: ܝܘܚܢܢ; Ge'ez: ዮሐንስ; Arabic: يوحنا الإنجيلي; Latin: Ioannes; Hebrew: יוחנן; Coptic: ⲓⲱⲁⲛⲛⲏⲥ or ⲓⲱ̅ⲁ[citation needed]

- ^ Since the 18th century, the Decretum Gelasianum has been associated with the Council of Rome (382), although historians dispute the connection.

References edit

External links edit

- "Saint John the Apostle." Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Answers.com

- St. John the Evangelist at the Christian Iconography web site

- Caxton's translations of the Golden Legend's two chapters on St. John: Of St. John the Evangelist and The History of St. John Port Latin